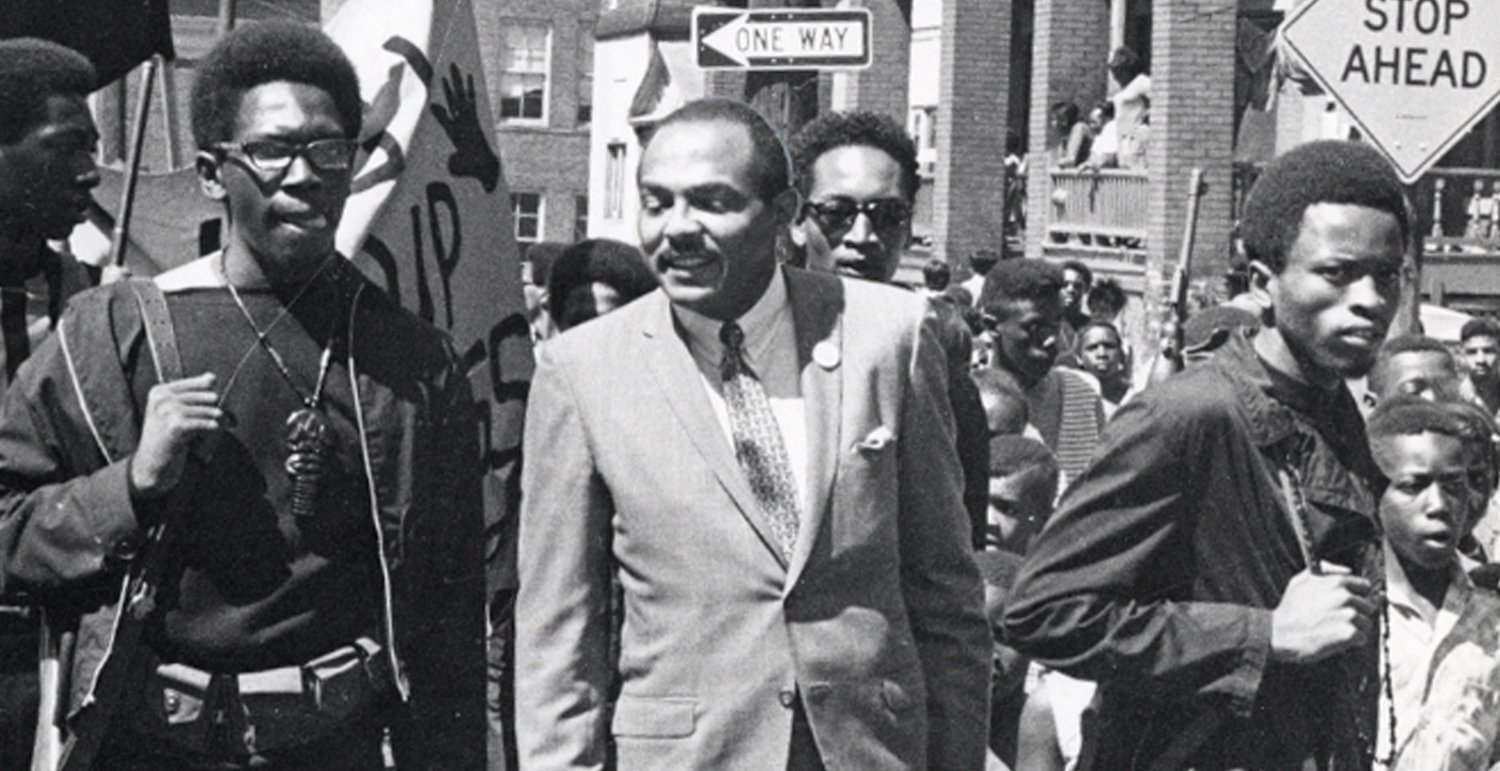

Police surveillance photo, Saturday, July 20, 1968, three days before the shootout. Mayor Carl Stokes in suit stands near Harllel Jones, leader of the Afro Set. The man in the center of the photo is Sababa Akili, a member of the Afro Set. Note the rifles. This is the kick-off of a parade commemorating the Hough Rebellion, which occurred two years earlier. Credit: Cleveland Police Museum

On July 23, 1968, police in Cleveland battled with black nationalists. The dramatic shootout in the Glenville neighborhood left ten dead and over fifteen wounded. The event sparked days of heavy rioting and raised myriad questions. Were these shootings an ambush by the nationalists? Or were the nationalists defending themselves from an imminent police assault? Mystery still surrounds how the urban warfare started and the role the FBI might have played in its origin.

Cleveland's story intersected with some of the most important African American figures of the time. Dr. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X both came to Cleveland, shaping the debate over how to address systemic racism. Should it be with nonviolence or armed self-defense? Malcolm X first delivered his iconic "The Ballot or the Bullet" speech in Cleveland. Three years later, in 1967, Carl Stokes, with King's help, became the first black mayor of a major US city. The ballot seemed to have triumphed over the bullet—and then Dr. King was assassinated.

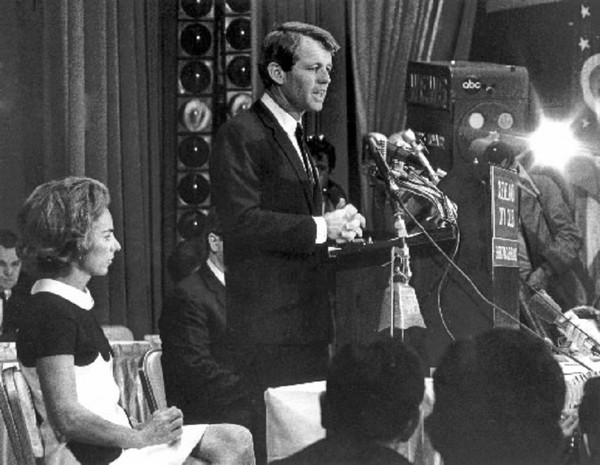

In the spring of 1968, while Mayor Stokes kept peace in Cleveland and Bobby Kennedy came to deliver his "Mindless Menace of Violence" speech, nationalists used an antipoverty program Stokes created in King's honor to buy rifles and ammunition.

Ballots and Bullets examines the revolutionary calls for addressing racism through guerrilla warfare in America's streets. It also puts into perspective the political aftermath, as racial violence and rebellions in most American cities led to white backlash and provided lift to the counterrevolution that brought Richard Nixon to power, effectively marking an end to President Johnson's "War on Poverty."

Fifty years later, many politicians still call for "law and order" to combat urban unrest. The Black Lives Matter movement and continued instances of police misconduct and brutality show that the cycle of race-based violence continues. The root causes—racism and poverty—remain largely unaddressed.